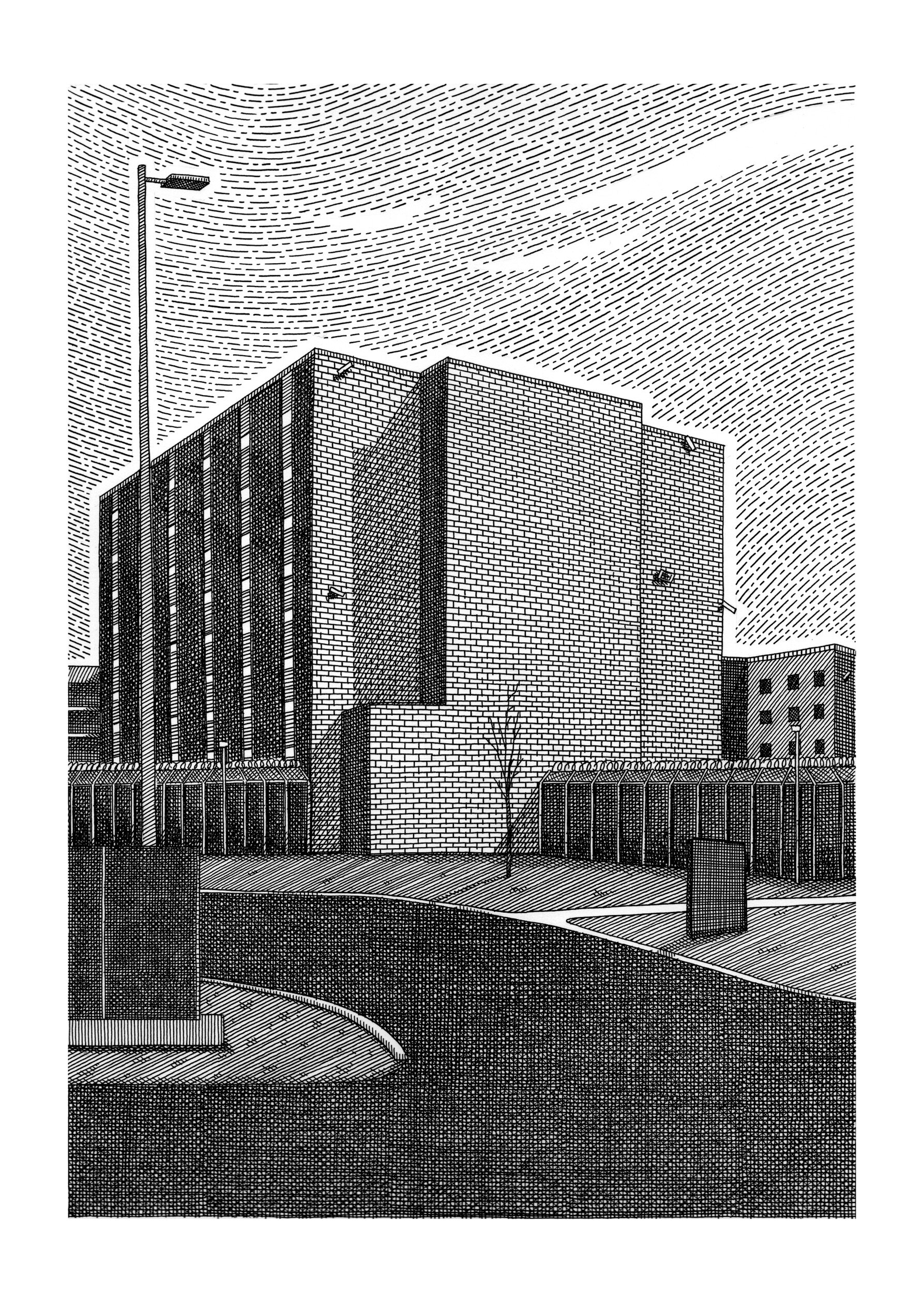

Reimagining the Nature of Youth Custody

• Illustration by Bren Luke

Detention isolates young people both physically and psychologically. In response, designers and social enterprises are using space and community to reimagine the nature of youth custody.

Youth detention has rarely received more attention in Australia than in recent years, drawing serious attention to the policies and design surrounding youth and juvenile detention. In Victoria, youth crime has been put in the spotlight, accompanied by much racism in mainstream media. Across Australia, the injustices experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and asylum seekers, held in indefinite detention on Nauru, have been scrutinised by royal commissions and human rights committees. In general, Australia’s treatment of children and young people in detention has been found to breach international and national standards. Questions are being asked about the disastrous impact detention can have on children’s mental health, and why the effectiveness of rehabilitation programs is declining. These issues are being addressed through design, art and skills training both in Australia and worldwide.

In 2017, the National Gallery of Victoria launched the Victorian Design Challenge, which invites multidisciplinary teams to use design to target real-world problems. The NGV and VicHealth asked design teams to address the question of how to “increase the resilience of today’s young people”. Architecture graduate Matt Dwyer and population and global health expert Dr Sanne Oostermeijer won the challenge with their project Local Time, which proposed new, localised design standards for the juvenile justice system’s residential diversion programs.

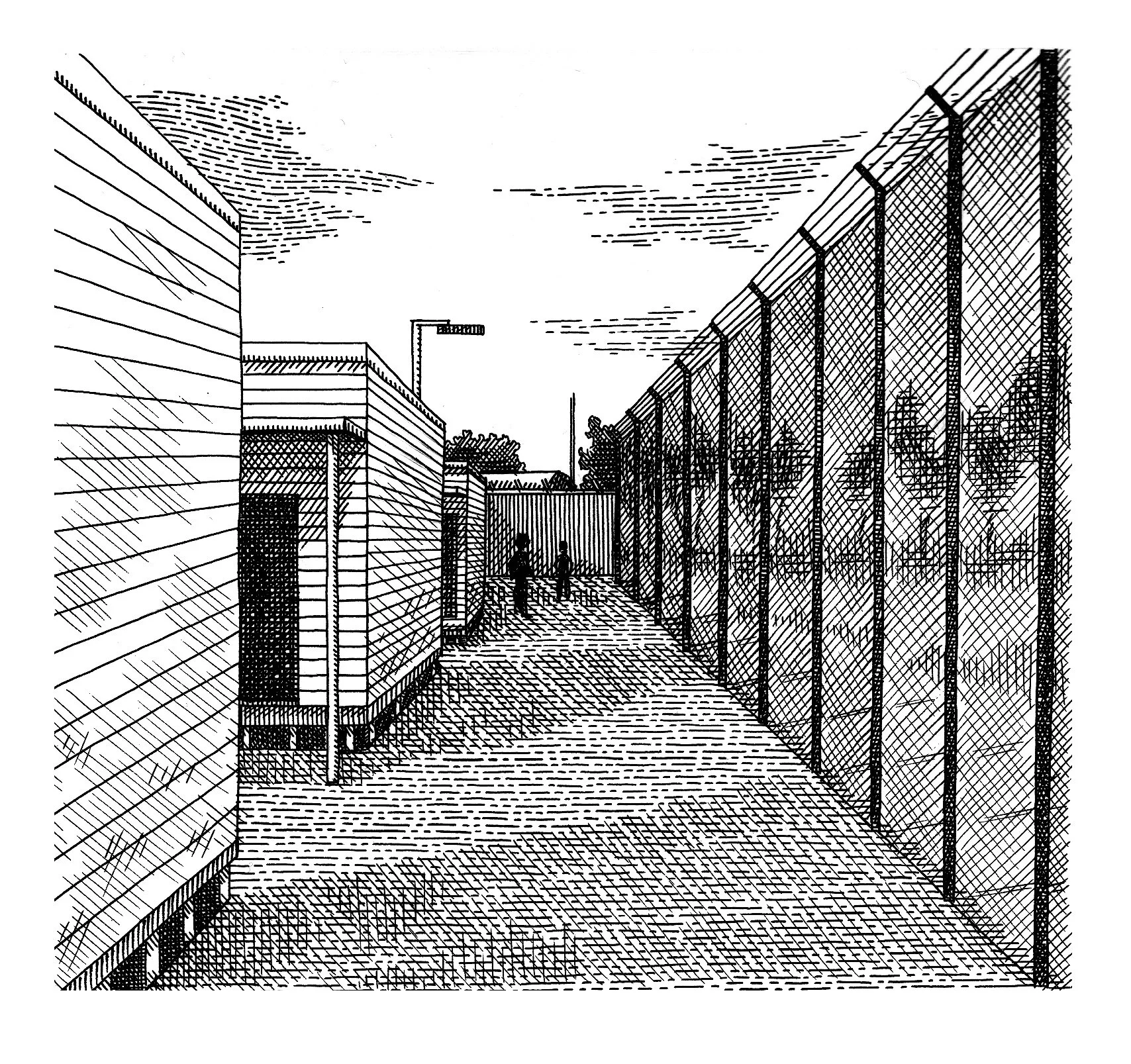

Oostermeijer says current design standards for Victorian detention facilities are focused on providing large-scale institutions on expansive greenfield sites – undeveloped land at a distance from existing towns or cities. These detention facilities, says Oostermeijer, have a long history of being designed to segregate. “For Victoria this includes the excessive use of isolation and high-incidence of injuries as the results of assaults in custody. It has been estimated that in Victoria 61 percent of young people return to detention, which shows that the system is not doing what it is meant to do.”

Local Time developed principles and standards for government bodies and architects to create small-scale, temporary housing for detention facilities. This approach offers young people vital access to their families and employment options as well as mental health and education services, with the aim to counter isolation.

While Victoria has lower numbers of young people on remand or serving custodial sentences than other states, a growing number of individuals are responsible for a disproportionate number of violent offences. According to a 2017 Victoria Parliament youth justice research paper, this has resulted in an “unprecedented proportion” of young people in detention, which poses management challenges and complicates the rehabilitation process. Paper author Caitlin Grover notes that youth justice is complex and distinct from the mainstream criminal justice system, involving issues of systemic disadvantage, rehabilitation and the human rights of children and young people. Investigations conducted by the Victorian Ombudsman and the Commissioner for Children and Young People, among others, found juveniles in detention were living under conditions that breached both Victorian law and the state’s Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities.

Grover argues that diversionary programs, which avoid the courts and detention, are fundamental to reducing recidivism, or reoffence. But access to diversion and bail support programs outside of major cities is limited.

In her work, Oostermeijer focuses on local solutions and the promotion of service integration in juvenile justice and mental health care systems. From 2016 to 2017 she helped investigate a “radical policy reform” in the Netherlands’ juvenile justice system, helping to improve local treatment for youth offenders.

• Illustration by Bren Luke

Back in Melbourne, social enterprise STREAT works directly with at-risk, marginalised and disadvantaged people aged between 16 and 24 – many of who have experienced first-hand the effects of youth detention. About 40 percent of STREAT’s trainees have had contact with the justice system before joining the hospitality-based organisation. The STREAT youth programs team says incarceration can impact young people’s physical and mental health, as well as their psychosocial skills and future wellbeing.

Ahmed, a 2015 STREAT graduate, arrived in Australia after fleeing Afghanistan alone as a young person. He survived a boat wreck that left many others dead.

“When I got to Australia I spent many months in different detention centres,” he says. “Those months were strange months... I felt relief because I was alive. Fear because so many people around me had already been waiting for so long. Anger that I was still confronted with men with guns who seemed frightened of us or worried that we would escape and do something.”

Ahmed says he experienced survivor’s guilt while he grieved for those who had died.

“Mostly I felt sadness because I was alone,” he adds.

But he says he found a community in Melbourne after joining STREAT, and now works in hospitality. STREAT says their trainees become “work and life ready” during a six-month integrated program that offers social connections, hospitality vocational training and on-the-job work experience, with transition support into open employment. The organisation points to a 2018 Victorian Auditor-General’s Office report, which found that 51 percent of young people in detention did not have a case plan.

People in detention experience higher levels of mental health issues than the general public, Oostermeijer says, which makes service provision vital.

“Elements such as education, family and employment are important for every young person in our society, but these elements are disrupted when a young person enters into remand or detention, which further disadvantages them.

“Locality is crucial in maintaining and strengthening existing social supports between young people and their family, school, employment and community. Small-scale facilities support a person-centred, relational approach to both security and care. These two elements are both procedural and spatial, requiring a considered and supportive physical environment for success.”

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth, dislocation from their communities and culture can be particularly devastating. But in Australia, Indigenous youth make up more than 50 percent of children in detention. In 2017, the Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory found that the cultural needs of children and young people in detention were ignored. With detention facilities often long distances from their communities, young First Australians are deprived of their culture. The Ngaga-dji (Hear Me) project gives Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who have experienced Victoria’s youth justice system the opportunity to voice the stories “that society silences with incarceration and stigma”.

Binak, one of the voices behind these stories, was removed from her family and placed in a state residential facility. “They said I’d be better off away from family,” she says. “They got it backwards, family was the one thing holding me together.” After multiple desperate attempts to flee the facility and return to her Nan, Binak was charged and ended up in the Koori Court, which involves community, family and elders in the decision-making process.

“An uncle at Koori Court told me that my family and culture are healing, that Nan and me have lots going on and need support so I can get to school, out of trouble and Nan can have a break,” Binak says. “There are no cultural programs for girls in this town, so an aunty from Koori Court is teaching me to weave, sharing stories with me. They might seem like little things but they’re bringing all my pieces together.”

“We wanted to get [the children] out of the war state of mind.”

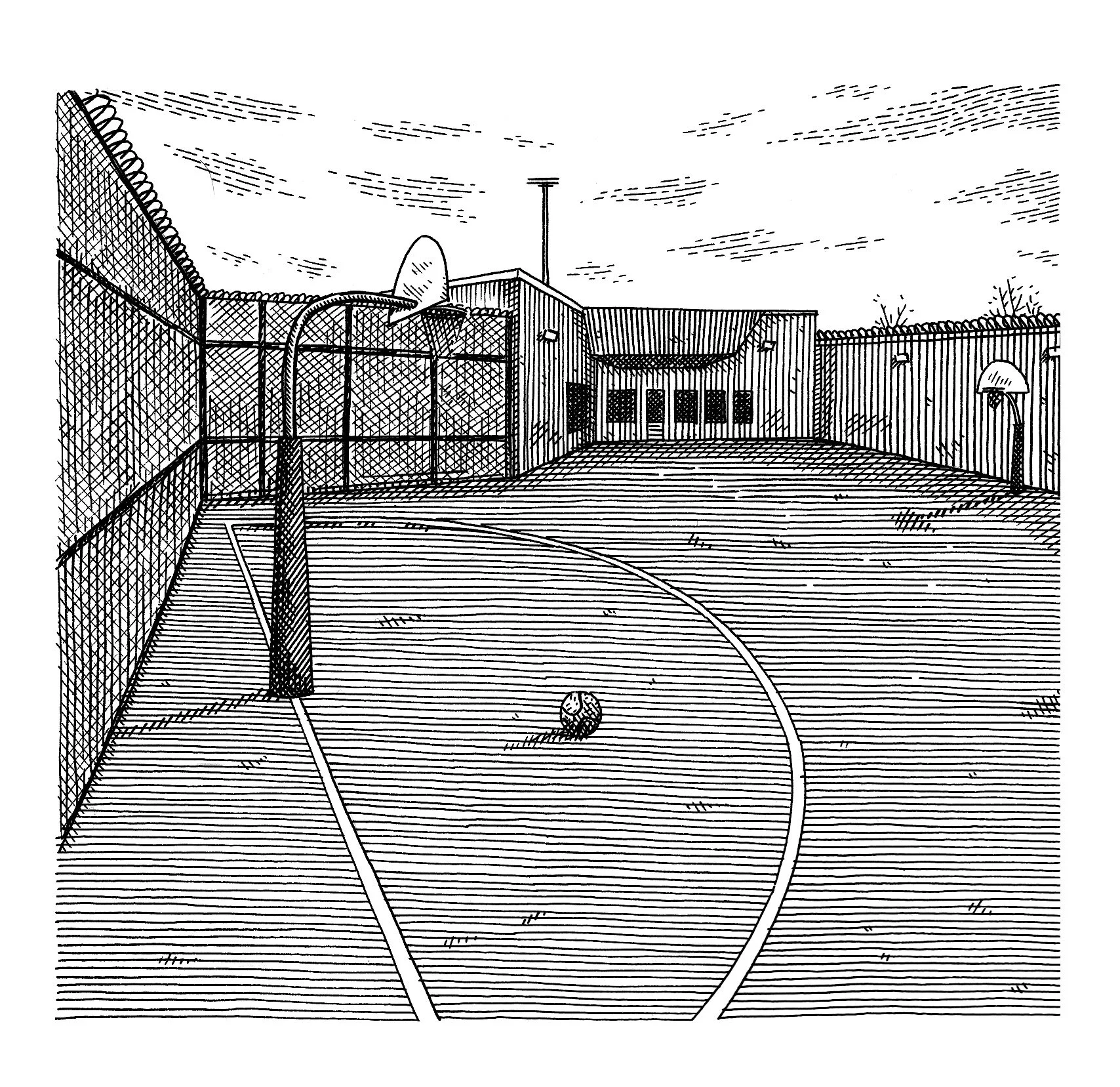

• Illustration by Bren Luke

Isolation of young people isn’t restricted to the mainland. Australia’s immigration detention facilities are designed to isolate detainees. According to the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre, one in four asylum seeker children detained on Nauru are suicidal. Natasha Blucher, ASRC detention advocacy manager, says there is an ongoing mental health and medical crisis for children on Nauru. “We are seeing cases of children who have stopped eating and babies who are not interacting because of the traumatic living conditions of offshore processing on Nauru.”

Human rights commissioner Gillian Triggs’ 2014 inquiry found that children detained indefinitely on Nauru suffered from extreme levels of physical, emotional, psychological and developmental distress. Abroad, many psychosocial therapy programs are working with disadvantaged and traumatised young people – many of them refugees and asylum seekers – to prepare them for adulthood.

In Lebanon, a number of groups have been working with Syrian refugee children since at least 1.5 million Syrians fled across the border into Lebanon after the outbreak of war in 2011. After a chance meeting, emeritus professor and composer Nigel Osborne joined forces with Driss Ben-Brahim, founder of the Kentara foundation, and Dr Rouba Mhaissen, founder of Lebanon’s Sawa for Development and Aid, to launch the Harmonic Education Program. Syrian music, arts and sports are used to teach core schooling material to refugee children, all with the aim of supporting students coping with trauma. Workshops are structured around the senses of sound, sight and motion, and the study of science and modern technology. But beyond that, the program allows students time to get in touch with themselves, their cultural history and their new environment.

Music teacher Ghayath Kana’a says there were many difficulties in the beginning. “We wanted to get [the children] out of the war state of mind,” he explains. “I’m not talking about music therapy. Our goal was to invest their energy, whether it was negative or positive, in music.”

The first cohort spent a year learning and honing their multidisciplinary talents before performing in 2016 at the Lebanese American University, one of the Middle East’s premier universities. For the 50 performers, it was the first time they had left their refugee camps in the Beqaa Valley.

“We’ve got the most fantastic team of young people, young Syrians, themselves refugees,” Osborne says. “We worked with them to help them develop their skills, but they’ve taken the project and made it entirely their own.”

The children’s emotions during the performance were palpable. During the first performance of traditional Syrian folk songs, the children began to cry, one after the other, until they had all left the stage. A teacher followed them while another explained to the audience how difficult the year had been, but how determined they children were to show what they had learnt. The children returned to the stage, clutching tissues and each other while the audience cheered them on through their own tears. The performers’ concentration as they formed human pyramids, and their joy at their success, were as unmistakable as their earlier sadness had been.

Social enterprises and creative endeavours can go some way to making up for the damage caused by governments’ treatment of children and young people in detention. Osborne says music, physical activity, theatre and dance are powerful ways of releasing tension and helping the body to regulate itself. The focus is on self-discovery, connecting with nature and experimenting with sound and light. This offers the space for children to allow their minds and souls to, once again, be free.