An Illustrated History of Fermenting

Pickles.

• Illustrations by Fran Murphy

Words by Renata Carli

Illustrations by Fran Murphy.

This story is brought to you by our partner Activated Probiotics

From kimchi to mead, humans have been fermenting for almost as long as we’ve been making food. But while the process is ancient, fermenting techniques established thousands of years ago are still being honed and studied today, while some are just being unearthed.

What is fermentation?

The word “fermentation” has its roots in the latin “fervere”, meaning to boil, bubble or seethe. Offshoots of this etymological branch are alive and well in today’s English – our word “fervent” evokes some of the effervescent frenzy that occurs when we ferment food.

Broadly speaking, fermentation happens when organic matter is converted to energy by enzymes produced by living microorganisms like yeasts, bacteria and moulds. When we’re talking about food, fermentation refers to the breaking down of food substrates into non-toxic or even healthier by-products. Microbes metabolise just like we do, converting complex molecules into simpler compounds and nutrients. They are our tiniest friends – they help us out by pre-digesting foods, making them more easily absorbed into the human body and enriching them with protein, vitamins and amino acids.

Where did it all begin?

The history of fermentation starts long before kimchi and miso, dating back billions of years. Since it’s an anaerobic process – meaning it requires no oxygen – it occurs in most bacteria, making it the world’s oldest metabolic pathway.

But let’s skip forward a little. The friendship between man and microbe is an ancient one. Almost every culture seems to have adopted fermentation as a way of preparing foods. Humans are thought to have been fermenting since the dawn of agriculture – from Neolithic times, or perhaps before. Back then, the goal was more to preserve foods or make them edible than to promote a healthy gut. Still, with evidence that Neolithic humans fermented grains like sorghum to make leavened bread, the practice has always been an important part of our lives.

A need for mead

One of the oldest traceable fermented substances and possibly the world’s oldest alcoholic drink is mead. Its earliest known description appears in the Rigveda, a collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns written around 3,700 years ago. And it seems a lot of other cultures also share an historic love of making fermented drinks. The Sumerians had a goddess, Ninkasi, devoted to beer and the fermenting process behind it, and it’s assumed that what the ancient Greeks called “ambrosia” — nectar of the gods — was, in fact, mead.

Ancient Egyptians produced mead and thought it had aphrodisiac properties, perhaps because they were drunk. It's been proposed that the word “honeymoon” refers to the fermented honey drink and its impassioned aftereffects. Not much is known about the early methods of making mead, but it’s likely gatherers would collect honey in animal hide sacks and then store them away. Yeast cultures present within the hide would mix with sugar from the honey and start the bubbly fermentation process. The Egyptians, by the way, loved their fermentation — evidence of industrial breweries has been found at archaeological sites, and it’s said that Egyptian queen Cleopatra attributed her beauty to eating pickles.

Quandongs.

• Illustrations by Fran Murphy

Ancient fermentation in our backyard

When we think about ancient foods, we often overlook the history hiding in our own backyard. It’s very possible that Australian First People practised fermentation long before the importation of alcohol by European colonisers. A 2018 research group studied a cluster of native plants across the southern regions of Australia, including cider gum and quandong roots, examining their microbiology, strains of yeast and bacteria that would have made fermenting possible. Cider gum sap in particular, abundant and high in sugar content, would have made an ideal ingredient – tapping the gums and allowing their rich sap to collect in bark among natural yeasts would produce a cider-like beverage.

Indigenous fermentation practices in pre-colonised Australia may have been ahead of their time, with one study suggesting the Noongar people of southwestern Australia soaked and fermented the sarcotesta (the fleshy seedcoat) of the Macrozamia plant. The study proposes the Noongar people possessed specialised knowledge of its nutritional value, as well as a diverse gut microbiome that had adapted to store quantities of nutrients and tolerate trace toxins present in fermented Macrozamia sarcotesta.

Around the same time, Native Americans were developing their own unique fermentation practices. Later reports describe some pretty novel recipes, from a fizzy kombucha made by mixing little balls of corn dough with saliva, to a kind of stew of half-digested food and blood, boiled and left to ferment inside a caribou’s stomach. Over in West Africa, things were a little less visceral. Ancient fermented foods like ogi – maize or sorghum – and gari – cassava root – are still prepared today, treasured for their cultural tradition and host of health benefits, which include inhibiting tooth decay, weaning infants and encouraging milk production in new mothers. Fermented foods with probiotic properties have also helped communities without access to antibiotics to stave off disease.

Fermented fish as a delicacy

Across Asia, fermenting has long been used to preserve perishable foods like fish while retaining or enhancing their health benefits. One of the oldest forms of fermented fish is kapi, shrimp paste that originated in the southeast. As early as the eighth century, inhabitants of modern-day Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore would harvest freshly hatched shrimp and dry them on bamboo mats in the sun. This method preserved the shrimp for months, sometimes years, and proved useful in balmy equatorial environments where food would otherwise go off quickly. We now know that the enzymes in shrimp paste help promote heart health, lower cholesterol and break up dangerous blood clots in the veins.

Later on, as the medieval age dawned and the Sukhothai kingdom was established, inland versions of kapi were made from river fish. The fish was placed in clay jars with salt and roasted rice and left decompose. As the fish broke down, it began to pickle, and the resulting paste was a delicacy among the Siamese elite, relished for its flavour and health benefits. Fermented fish wasn’t for everyone — some contemporary travellers to the region thought of it as “rotten” — but shrimp paste prevails as a staple of Asian cuisine, forming the basis of kimchi, sambal and various curry pastes.

• Illustration by Fran Murphy

Dairy me

One of the most enduring uses for fermentation is making cultured dairy, which has become a daily component of diets across the modern world in the form of cheeses, yoghurts and kefir. Of those, kefir is perhaps the richest in health benefits and in history. So old that it predates written history, kefir originated among tribes of the Caucasus. Despite its age, it wasn't made commercially in Russia until the early 1900s, when Moscow Dairy sent a beautiful young employee, Irina Sakharova, to the Caucasus mountains to charm a local prince into handing over his kefir grains. The plan didn’t work out so well for Irina, who was kidnapped by the besotted prince. But it was a blessing for Russians; they eventually received the grains along with the safe return of Irina, and kefir quickly became the country’s fermented drink of choice.

Nowadays, the average Russian consumes 20 litres of kefir a year. The drink is so packed with goodness that it was used in Soviet hospitals to treat serious illnesses like atherosclerosis, tuberculosis and cancer. Kefir was a subject of fascination for Dr. Elie Metchnikoff, a Nobel prize-winning Russian immunologist who noted that people from the Caucasus region had an exceptionally high life expectancy. Metchnikoff supposed their longevity was due to the consumption of kefir and the probiotic bacteria it's jam-packed with. Even after modern advancements in medicine, the tremendous health impact of kefir can’t be ignored, with evidence constantly emerging of its benefits. Among other advantages, it can mitigate symptoms of metabolic syndrome that arise from our increasingly urbanised lifestyle, like insulin resistance and hypertension. The word “superfood” might be overplayed, but kefir is one menu item that's deserving of the label.

Science or art?

In the 1800s, human curiosity and advances in science kicked off a series of investigations into the world of fermenting. French chemist Louis Pasteur founded the field of zymology, the study of fermentation, which he initially defined as “respiration without air”. That curiosity soon spread to Japan. Koji, mold-fermented rice or soybean, had been used to make staples such as miso and soy sauce for hundreds of years, but little was known about the science behind fermentation, about the 50-odd enzymes in koji or how they interacted with food. Then, in the Meiji era (not long after Pasteur was poking about the microbial realm), the country opened up to modernisation and contemporary science. European scientists began travelling to Japan and Japanese scientists to various pockets of the globe to study the fragrant mold that covers koji and its later fermentation. Universities were opened, patents were granted and Japan became a leader in the field of microbiology.

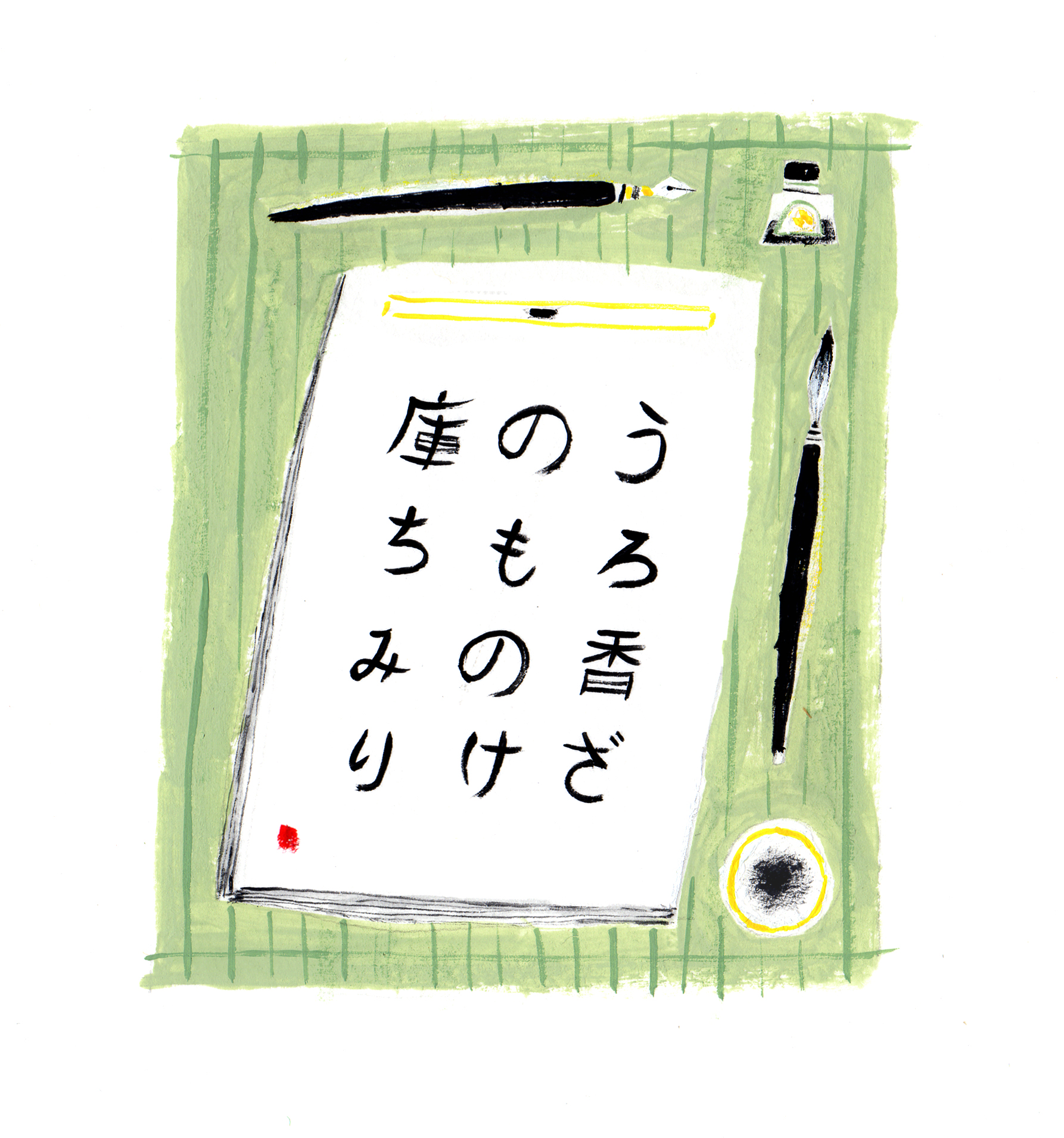

One of the koji-loving scientists to emerge amid this frenzy of new research was microbiologist Kinichiro Sakaguchi, who closely studied koji and collected over 3,000 samples from around Japan. Sakaguchi was completely immersed in his field and saw the microscopic world as a source of constant wonder, at one point remarking, “I have never been disappointed upon asking microorganisms for whatever I wanted.” Sakaguchi was also a writer of traditional waka poetry and in the 1970s found a rather unique muse in fermentation — not the end product but the process itself. In one poem translated by Mark Knight, he wrote:

From the kura

The aroma of fermenting mash

Wafts boldly out

To the garden

Where a plum tree is in bloom

Fermenting today

Today, the idea of fermentation as an art form has been carried on by traditional makers and new thinkers alike. In 2014, Copenhagen restaurant Noma opened its fermentation lab, a probiotic wonderland that frequently blurs the line between food, science and art. The lab produces everything from coffee kombucha to lacto-fermented mushrooms and published The Noma Guide to Fermentation. In it, chef David Zilber draws a parallel between seething enzymes and the chaotic behaviour of the universe. Referring to miso, he explains how “minute details” and random variables in the making process can influence the final product in surprisingly significant ways. Even bacteria on the maker’s skin can alter the taste. Zilber likens it to the butterfly effect — “it’s what makes fermentation unpredictable and thrilling”.

True to its etymological roots, the fermenting craze is bubbling away and shows no sign of dying out. There’s mounting awareness of the health benefits as research in the field grows, building on ancient knowledge to explore the specific healing potentials of probiotics, from treating asthma to boosting mood. It’s hard to say whether or not our ancient ancestors knew that the microbe-rich foods they handed down for generations came with the happy side effect of promoting gut health, but either way, their traditions have stood the test of time.